Here’s why most writing advice is not merely pointless, but corrosive.

A lot of the things we think we know or believe are simply grammatical residue.

A classic example: “It is raining.” There is no “it.” It only exists grammatically. Yet, we come to believe in an it. And then illusions of agency haunt our understanding of the weather.

Another: “The wind is blowing.” What else would the wind be doing if it weren’t blowing? Yet it needs a verb to complete the grammatical pattern.

We learn that a noun is a person, place, or thing, when all along, it is none of those things, but rather a process. The wind isn’t a thing at all. Nothing is. You have to think it through to see it with less distortion.

One practical implication is that grammar is always an approximation—whether it’s used to describe ordinary usage or prescribe correct usage. Just as often, schoolmarmish grammatical rules are typically wrong. People tell you not to end a sentence with a preposition, not understanding that parts of speech in English are fluid and that a preposition can be used adverbially. People tell you not to use adverbs, while, absurdly, “not” itself is an adverb.

Getting these things right matters because it’s the difference between grammatical residue impeding what you mean and the use of grammar to add meaning.

Another implication is that formulaic stylistic advice and writing tips are equally misguided. But the problem isn’t the validity of the individual bits of trite detritus. It’s that they impose a distorted view of things, just like grammatical residue.

And these waste products don’t just sit there. They curdle. They lure insecure writers and communicators and lead to abominations.

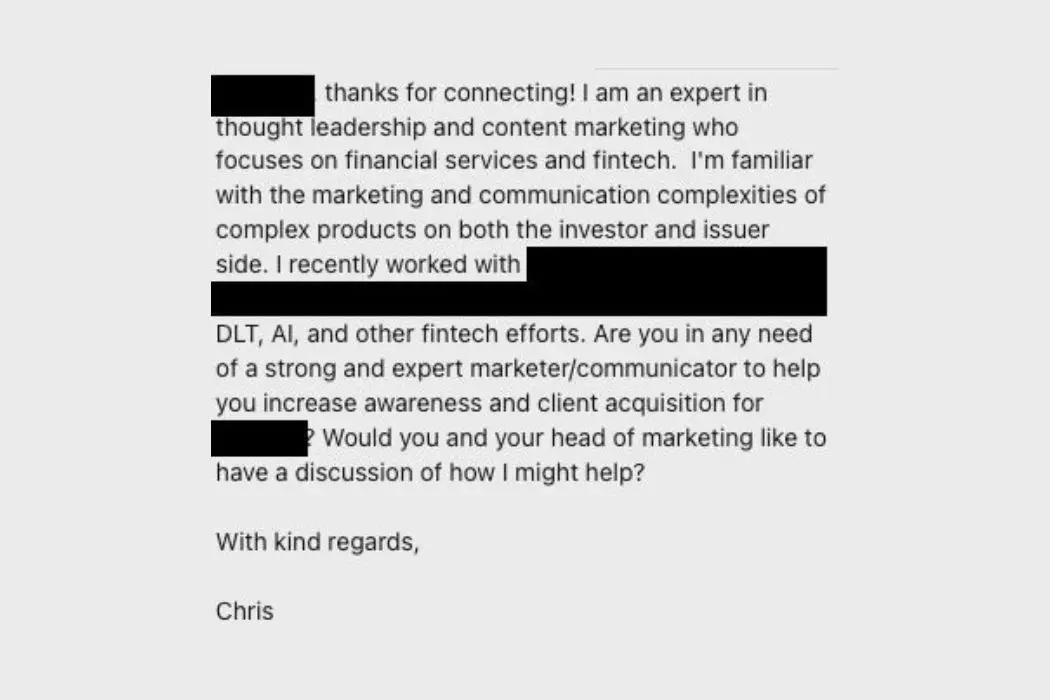

The pessimum of these—believing in “content.” That mindset rots your message and purpose from the inside out.