Hear the phrase “eating content” in 2024, and you’re likely expecting a screed against AI. But that’s not it.

Whether AI replaces human creators or not, the whole notion of content and content creators is being aggressively undermined and hollowed out by forces that have been accumulating for many years.

Although I’m primarily speaking about written content, speaking from a place of two decades of experience, I’m morally certain that what I’m describing applies to other formats as well.

In fact, part of the disease wasting away creative work is the use of a term like “content” to corral and diminish—or “manage”—it as undifferentiated goo. Content is destroying itself.

What’s in a word?

I am so repulsed by the word “content” to describe creative work that I almost struggle to put it into words. What I believe, first, is that the word betrays a mentality of disrespect and disdain for humanity.

Like the word “stuff,” which I’d honestly prefer, it reduces what it describes to something that only exists to fill up space. It’s a synonym with a difference.

Words like “text” or “audio” at least acknowledge that something might have formal replace-word properties and that it connects in some way to human perception, seen with the eye, heard with the ear, felt with the body.

There is form.

Words like “essay” or “song” imply that a reader or listener might exercise some degree of judgment, might experience the aesthetic properties of what they encounter.

There is beauty.

Words like “writing” or “speaking,” by virtue of their formation from verbs, include the role of human agency. It takes someone with some level of intersubjective intent.

There is meaning.

However, using the word “content” occludes form, beauty, and meaning.

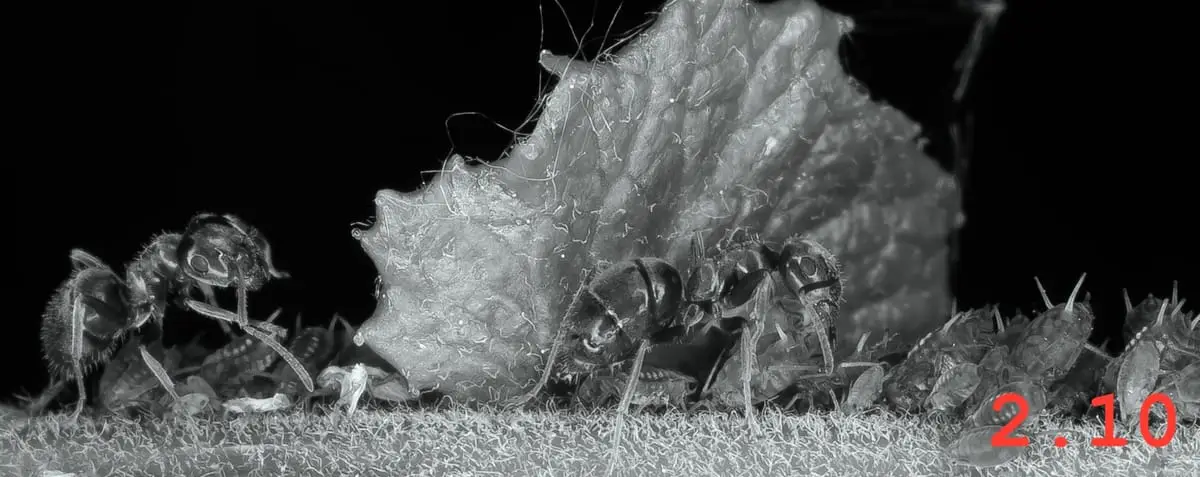

It’s the same life-hating maneuver as calling animals “livestock,” calling nature “biomass,” or calling humans “resources.” These words eviscerate the wholeness of what they describe and reduce them to fodder for industrial management.

Perhaps as one of the human animals that such techniques set out to manage, I feel the offense more acutely. But you, as a consumer, should feel just as diminished, because in the factory farm system of content, you’re nothing but clicks and eyeballs. You’re stripped bare of your dignity as much as I am.

There’s a Wor(l)d for this…

How did we get here in the first place? I see it through the lens of one telling detail. Every year, there’s Content Marketing World. You know, just like Carpet World, Funeral Fair, or The World Toilet Expo. There’s also a Content Marketing Institute, like the Association for Crime Scene Reconstruction, or The Center for Prevention of Shopping Cart Abuse.

Those facts—and oh crap, now I’m never going to be invited to these shows—signal the bureaucratization of content.

Creating an imagined discipline is a watershed moment. The arc of organizations is long, but it bends towards bureaucracy. Micro-specializations tend to form between the organizational cracks. Then they wedge themselves in there.

The cracks get wide enough to make room for more, and all of a sudden, the people living in those cracks will defend them to death. If they can’t add value, they damn sure will create process.

It isn’t a malevolent plot. It’s just organizational psychology.

In reality, the only intermediation needed between a writer and an expert, a leader, or a business team is the process of publishing and distribution. Everything else is “make work.” But for reasons I don’t fully understand, beyond the tenacity of the dog who’s got a bone, once unnecessary steps and roles work their way into a process, it’s difficult to get them out.

Bleeding out the meaning

All of this is more than a matter of principle. The stakes go beyond the niceties of human dignity—if that’s not enough to care about.

The content mentality is divorced from context and meaning. That’s bad for business because it takes an exchange of meaning to initiate an exchange of value.

Because content professionals see content only for the sake of content, as undifferentiated goo to harvest and disseminate, they rarely have the knowledge to understand the intentions of an expert or author. They also rarely have the context to understand the audience’s world in any detail.

But they have to do something, so they focus on trivialities.

They often insist on making content, i.e., generic stuff, accessible to a layperson, i.e., a generic reader, in ways that diminish the credibility of something by and for a more sophisticated context of meaning.

Worse, they confect meaningless best practices that add noise to the message that needs to be delivered to help a reader make a coherent business decision.

I’ll admit that I’m picking an easy, straw version of the process and reducing it to absurdity.

At the same time, I know perfectly well that what I’m saying will sound familiar to most stakeholders who have participated in the process of crafting or contributing to written materials.

Containers don’t need us anymore.

Now, we get to the bit about AI. Generative AI can produce plausible enough sounding writing because it has been trained on a dataset that includes massive amounts of contentified writing, and because such writing is already more about formula than meaning.

The AIs learned it from us.

Moreover, AI reflects the suppressed subconscious of the content industry—infinite generation of supply without the mess of livestock, the mouths to feed, the stalls to clean.

This fantasy represents the pure dream of content, produced without regard for intersubjective intent.

Now, soon enough, the containers will be able to fill themselves with content, because “content” is a worldview that’s only about things to be contained, or rather, not even the things, but their containedness per se. Good luck to us when we’re on the receiving end of that feeding tube.

So what now?

We’re very far down this road.

Above all, we have to throw away almost 15 years of accumulated workflow and redesign the idea-to-publication process from zero.

But it’s a long path back from bureaucracy and industrialization. There are a few steps we can take to begin heading in the right direction.

Six interim steps

- Use the word content as sparingly as possible.

- Reestablish direct lines of communication between writers and business leaders.

- Shift the role of marketing to funding and orchestrating production, similar to a Hollywood studio.

- Redefine the roles of “content marketing professionals” to provide distribution to the right audience only—hands off creation.

- Support and incentivize the upskilling of people in content roles to develop fluency-level command of the language of relevant business domains.

- Refocus everything around the concepts of meaning, relevance, and decision-making, not generic best practices.

As for me, what’s next is simple. It’s taken me a while to gather the courage to tell these truths about content out loud. Now they’re out, and I can get back to work, writing with as much nuance and grace as possible, working with innovators who want to create meaningful change, and helping innovative clients turn their ideas into sources of growth.

No more, and no less than that.

Three Grace Notes

“Elite overproduction develops when the demand for power positions by elite aspirants massively exceeds their supply.” — Peter Turchin, End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration

“On the other side of our algorithmic anxiety is a state of numbness. The dopamine rushes become inadequate, and the noise and speed of the feeds overwhelming. Our natural reaction is to seek out culture that embraces nothingness, that blankets and soothes rather than challenges or surprises, as powerful artwork is meant to do. Our capacity to be moved, or even to be interested and curious, is depleted.” — Kyle Chayka, Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture

“Perhaps it is the fate of intellectuals who incautiously trust their thoughts to a wider public that those thoughts should be abducted and abused like a child of rich parents.” — William Gass, Life Sentences: Literary Judgments and Accounts

Note: The links above are affiliate links. I’m using them in lieu of paid subscription tiers or digital tip jars. Seems like a much more graceful way to generate financial support while sharing more thinking and writing that can guide thought leadership.